Smart Reply in Gmail

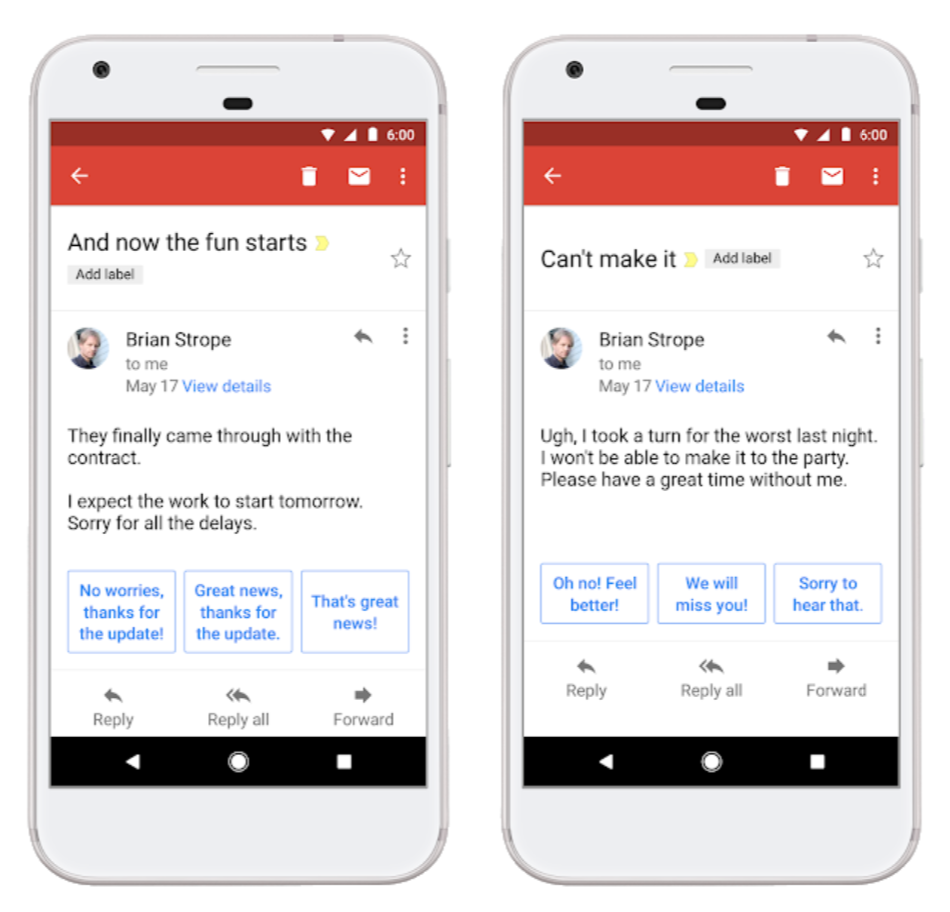

It’s pretty easy to read your emails while you’re on the go, but responding to those emails takes effort. Smart Reply, available in Inbox by Gmail , saves you time by suggesting quick responses to your messages. The feature drives 12 percent of replies in Inbox on mobile. And it has also been started for Android and iOS .

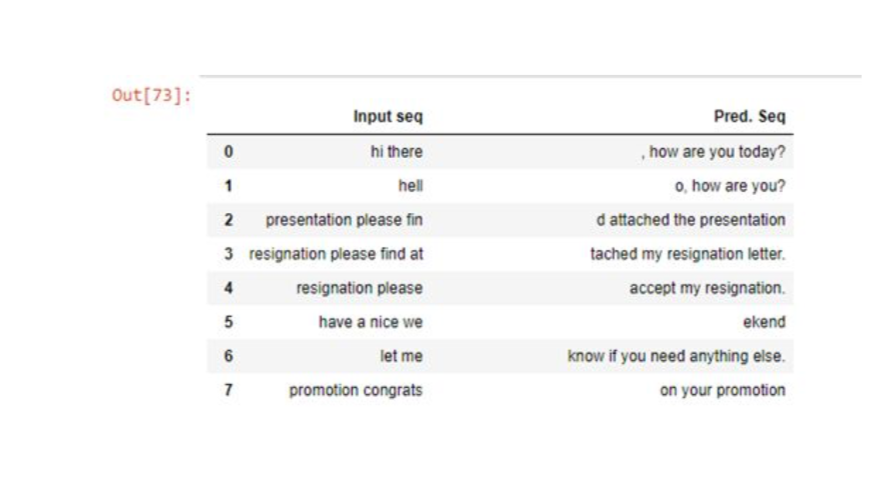

From the above we can see that the system can find responses that are on point, without an overlap of keywords or even synonyms of keywords.It’s delighting to see the system suggesting results that show understanding and are helpful.

Smarts behind Smart Reply

How does it suggest brief responses when appropriate, just one tap away?

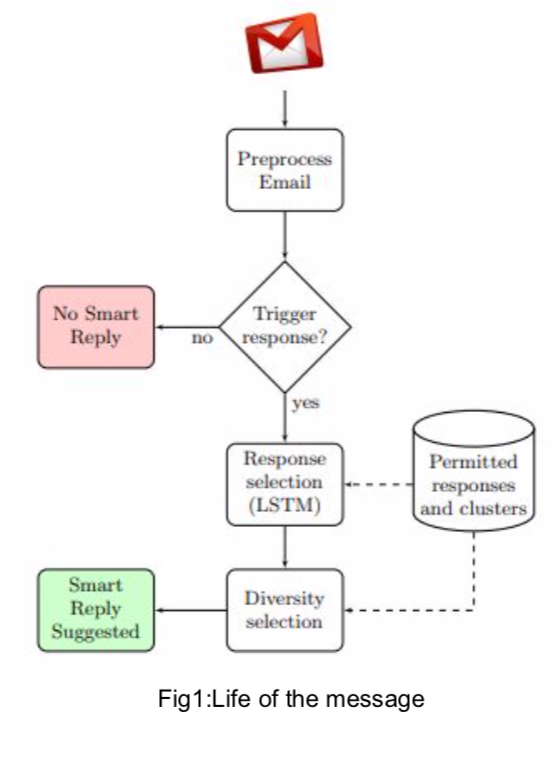

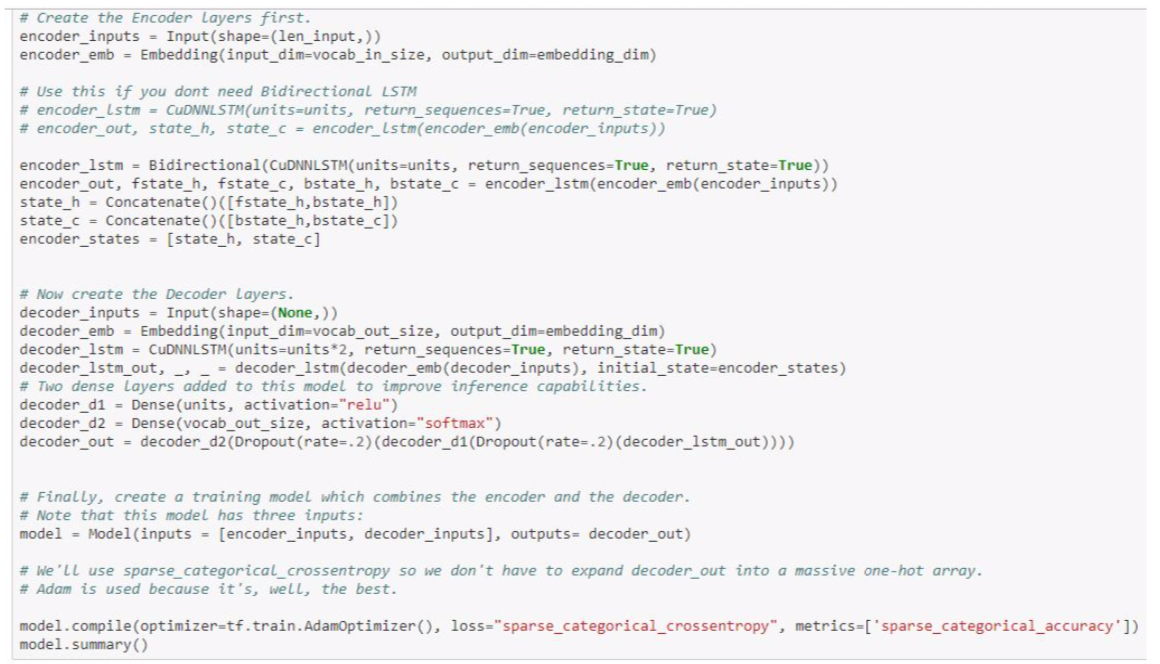

It uses the the sequence-to sequence learning framework , which uses long short term memory networks (LSTMs) to predict sequences of text. Consistent with the approach of the Neural Conversation Model,the input sequence is the content of the email and output being all possible replies.Smart Reply consists of the following components, which are also shown in Fig1

Pre-processing

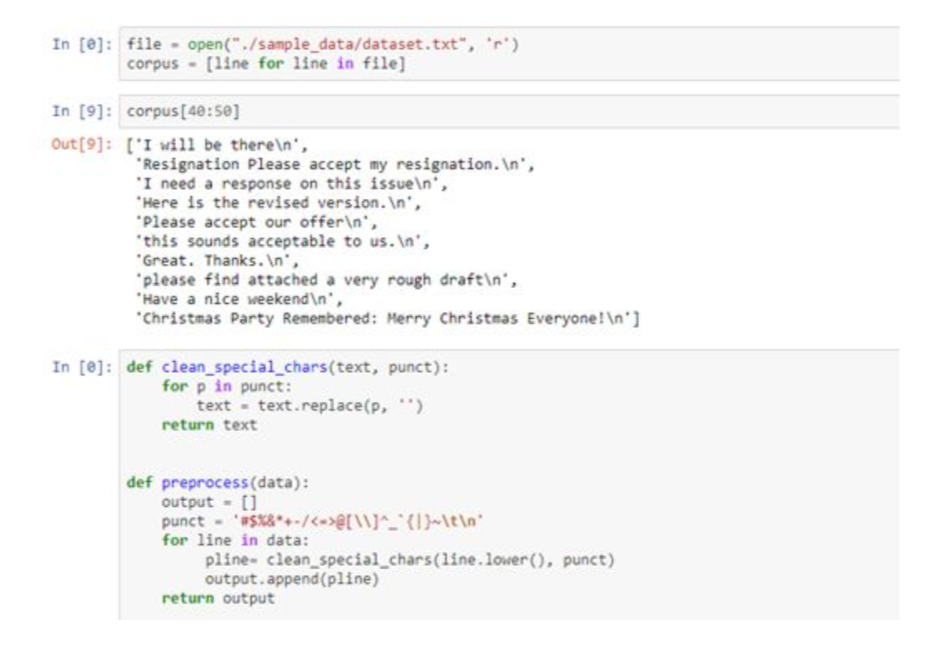

An incoming email message is pre-processed before being fed into the Smart Reply pipeline. Pre-processing includes:

● Language detection (non-English messages are discarded at this point, sorry).

● Tokenization of subject and message body

● Sentence segmentation

● Normalization of infrequent words and entities – these are replaced by special tokens

● Removal of quoted and forward email portions

● Removal of greeting and closing phrases (“Hi John”,… “Regards, Mary”)

For example, here first dataset is loaded and then cleaned and transformed into target dataset.

Trigger Response

Computing smart replies is computationally expensive (in the context of mass email delivery),so the next step on an email’s journey is the triggering module, whose job it is to decide whether or not to attempt to create smart replies at all. Bad candidates for reply generation include emails unsuitable for short replies (open-ended questions, sensitive topics…), and those for which no reply is necessary (promotional emails etc.).

Currently, the system decides to produce a Smart Reply for roughly 11% of messages, so this process vastly reduces the number of useless suggestions seen by the users.

The triggering component is implemented as a feed-forward neural network (multilayer perceptron with an embedding layer that can handle a vocabulary of roughly one million words, and three fully connected hidden layers). Input features include those extracted in the preprocessing step together with various social signals such as whether the sender is in the recipient’s address book or social network, and whether the recipient has previously sent replies to the sender. The training corpus of emails is also labelled to indicate those which had a response and those which did not.

If the probability score output by the triggering component is greater than a predetermined threshold, then the email is sent to the core smart reply system for response generation.

Following code helps in implementing Trigger Response

Response selection

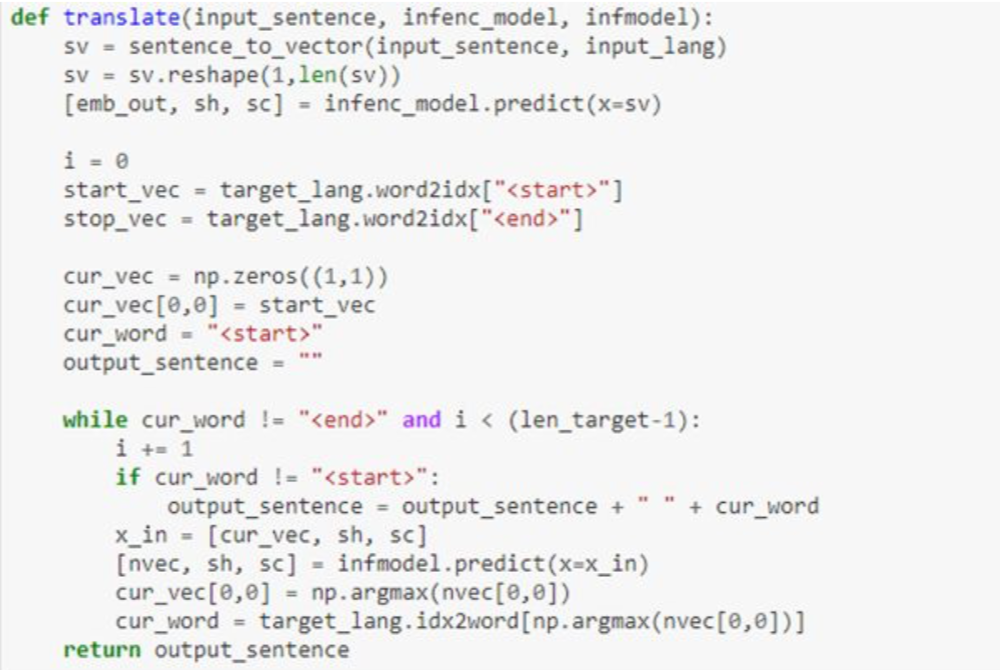

At the core of our system, an LSTM neural network processes an incoming message, then uses it to predict the most likely responses. LSTM computation can be expensive, so scalability is improved by finding only the approximate best responses.

First, the sequence of original message tokens, including a special end-of-message token on, are read in, such that the LSTM’s hidden state encodes a vector representation of the whole message. Then, given this hidden state, a softmax output is computed and interpreted as P(r1/o1, …, on), or the probability distribution for the first response token. As response tokens are fed in, the softmax at each timestep t is interpreted as P(rt/o1, …, on, r1, …, rt−1). Given the factorization above, these softmaxes can be used to compute P(r1, …, rm/o1, …, on).

Given that the model is trained on a corpus of real messages, we have to account for the possibility that the most probable response is not necessarily a high quality response. Even a response that occurs frequently in our corpus may not be appropriate to surface back to users. For example, it could contain poor grammar, spelling, or mechanics (your the best!); it could convey a familiarity that is likely to be jarring or offensive in many situations (thanks hon!); it could be too informal to be consistent with other Inbox intelligence features (yup, got it thx); it could convey a sentiment that is politically incorrect, offensive, or otherwise inappropriate (Leave me alone).

This requires a searching and scoring mechanism that is not a function of the size of the response set! The solution is to organise the elements of the response into a trie, and then use a beam search to explore hypotheses that appear in the trie. T his search process has complexity O(bl) for beam size b and maximum response length l. Both b and l are typically in the range of 10-30, so this method dramatically reduces the time to find the top responses and is a critical element of making this system deployable.

Ensuring diversity in responses

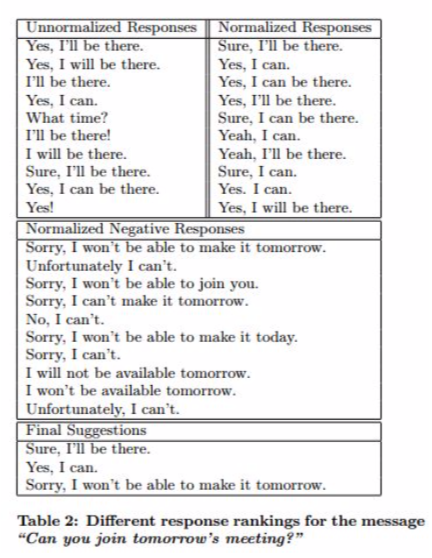

At this point we have an ordered list of possible responses, but it doesn’t make sense to just take the top three (Smart Reply only shows the user three options). It’s quite likely there is redundancy in the possible replies, e.g. three variations of “I’ll be there.”

The job of the diversity component is to select a more varied set of suggestions using two strategies: omitting redundant responses and enforcing negative or positive responses.

How is this done?

Responses are classified as positive, neutral, or negative. If the top two responses contain at least one positive response, and no negative response, then the third response is replaced with a negative one. (The same logic is also applied in reverse in the rarer case of exclusively negative responses).

Generating the response set in the first place

Response set generation begins with anonymised short response sentences from the pre-processed training data, yielding a few million unique sentences. These are parsed used a dependency parser and the resulting syntactic structure is used to generate a canonicalised representation. For example, “Thanks for your kind update”, “Thank you for updating!”, and “Thanks for the status update” may all get mapped to “Thanks for the update.”

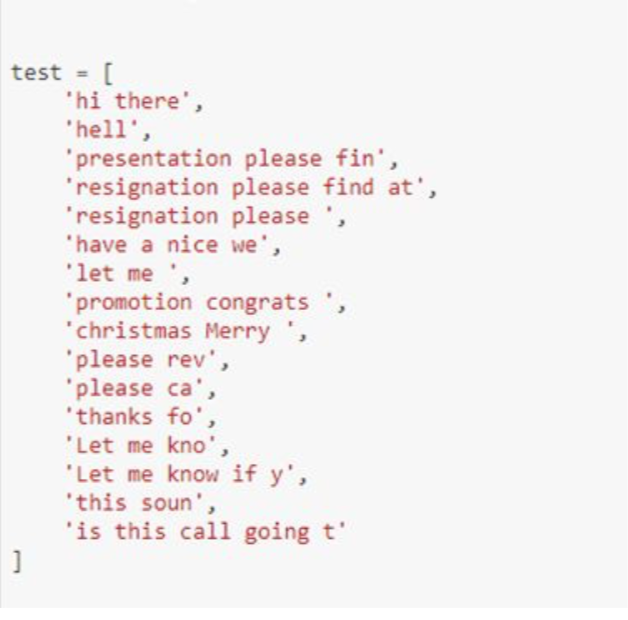

Consider the below figure which contains anonymised short sentences for testing the model

At the next step response are clustered into semantic clusters where each represents an intent. The process is seeded with a few manually defined clusters sampled from the top frequent messages.

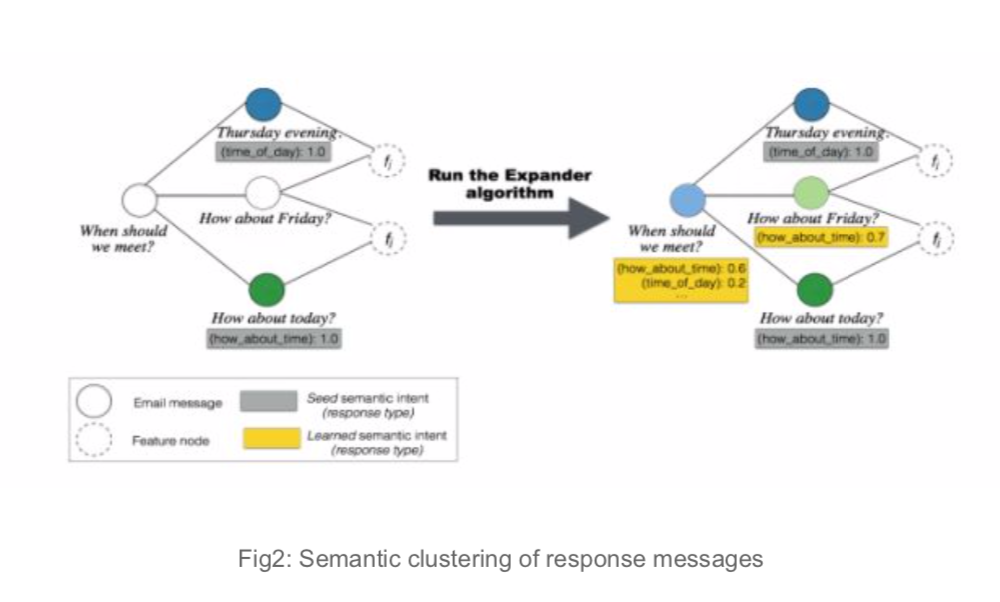

We then construct a base graph with frequent response messages as nodes (VR). For each response message, we further extract a set of lexical features (ngrams and skip-grams of length up to 3) and add these as “feature” nodes (VF) to the same graph. Edges are created between a pair of nodes (u, v) where u ∈ VR and v ∈ VF if v belongs to the feature set for response u.

From this graph a semantic labelling is learned using the EXPANDER framework. The top scoring output label for a given node is assigned as the node’s semantic intent. The algorithm is run over a number of iterations, each time introducing another batch of randomly sampled new responses from the remaining unlabeled nodes in the graph. Finally, the top k members for each semantic cluster are extracted, sorted by their label scores.

The set of (response, cluster label) pairs are then validated by human raters… The result is an automatically generated and validated set of high quality response messages labeled with semantic intent. Following code helps to get the desired smart reply